When I speak with colleagues about ways to provide primary care to the poor, they generally fall into one of two camps. The first camp, generally supporters of the Affordable Care Act, contends that the ACA's originally mandatory (but later ruled optional) expansion of Medicaid insurance eligibility and a temporary federally-funded increase in Medicaid fee-for-service rates to Medicare levels provided enough incentives to attract family physicians to patient-centered medical homes that primarily serve low-income patients. (Disclosure: about 15 percent of my current practice's patients have Medicaid.)

There is plenty of evidence that low-income residents of states that chose to opt out of Medicaid expansion will be worse off than those in states that have expanded their programs. Not only do people whose incomes are at or lower than federal poverty levels have less access to acute and chronic care, they receive less preventive care and are more likely to be sicker and die sooner than if they had Medicaid coverage. In addition, the Robert Graham Center has projected that fewer primary care physicians will practice in states that do not expand their programs, exacerbating existing workforce shortages. A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine reported that after Medicaid fee-for-service payments for primary care visits rose in 2013 by an average of 73 percent, it was significantly easier for simulated Medicaid patients to schedule appointments with doctors. Unfortunately, the federal Medicaid pay increase expired at the end of 2014, and only 15 states plan to continue the increased rates.

Most encouraging is a recent study in JAMA Internal Medicine that examined the association between patient-centered medical home implementation and breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening. Not only was having more characteristics of a PCMH associated with higher screening rates in general, larger screening increases in PCMH practices that served patients with lower incomes and educational backgrounds considerably reduced screening disparities between the rich and the poor.

All good news, but is this momentum sustainable, and is it nearly enough? Not a chance, say my colleagues in the other camp. In 35 states and the District of Columbia, Medicaid fees have reverted to their previous embarrassingly low levels, and the Supreme Court will rule this summer whether doctors and hospitals can sue state Medicaid programs for paying fees that are typically less than the cost of providing care. It gets even worse: in my practice, a large Medicaid insurer paid us nothing for several months, then negotiated a lump settlement with our parent institution that required the insurer to only to pay 40 percent of what it actually owed. If our practice had to rely exclusively on Medicaid for cash flow, it's hard to see how we could keep our doors open. And low-income patients who earn between 138% and 400% of the federal poverty level and receive federal subsidies to purchase health insurance on the marketplaces often face several thousand dollar deductibles, making them pay out of pocket for everything except preventive care.

So family physicians and other primary care innovators are taking matters into their own hands. For example, the "Robin Hood" practice model is a viable solution for patients who remain uninsured or underinsured after the ACA. The most-read guest post of all time on this blog explained how a direct primary care model can benefit low-income patients. For those who worry that a $50 monthly fee for unlimited primary care could be too much for patients living paycheck to paycheck, a leading direct primary care practice in Washington State now serves thousands of Medicaid patients through a contract where regular monthly payments flow directly to the practice rather than passing through an administrative maze of insurance claims for individual visits. After being slow to recognize these types of practices or dismissing them as high-end "concierge care," the American Academy of Family Physicians now offers a variety of helpful resources on direct primary care.

Given these developments, it doesn't make sense to me for physicians and policy makers to squabble about the "best" way to provide health care to the poor or continue to pine for a pie-in-the-sky universal system for all. The U.S. health care environment has always been complicated, and is even more so nearly 5 years after passage of the ACA. Physicians who dedicate themselves and their practices to caring for underserved and vulnerable populations should be supported however they choose to do so, rather than rebuked for thinking outside of a politically correct health reform box. The more creativity we can bring to bear on this issue, the better.

Tuesday, February 24, 2015

Saturday, February 21, 2015

Debating testosterone screening and therapy in older men

A good number of new patients to my practice are older men whose previous physicians have retired. More and more often, I've noticed while reviewing records from previous physicals that they have had their testosterone levels checked - usually without any documented rationale for doing so. In two Pro-Con editorials in the February 15th issue of American Family Physician, Drs. Joel Heidelbaugh and Adriane Fugh-Berman debate the merits and potential unintended consequences of screening for testosterone deficiency in older men. Dr. Heidelbaugh points out that observational studies have associated low serum testosterone levels with cardiovascular disease, cancer, impaired glucose tolerance, and metabolic syndrome. He further argues that symptoms of testosterone deficiency may be erroneously attributed to normal aging:

Although screening targets asymptomatic men, testosterone deficiency is unique because symptoms are not always well defined. This warrants casting a wider net to identify a treatable condition. Symptoms such as depression, fatigue, and inability to perform vigorous activity are related to low testosterone levels, whereas there is an inverse relationship between the number of sexual symptoms and testosterone levels.

These questions demonstrate how pharmaceutical companies use nonspecific symptoms to foster disease states and then convince physicians that these conditions are real. In this case, the disease state is marketed to consumers as Low T, and to physicians as late-onset hypogonadism.

Of observed associations between low testosterone levels and chronic diseases, Dr. Fugh-Berman counters that "association does not prove causation, and there is no reliable evidence that testosterone treatment improves any chronic disease."

Although screening targets asymptomatic men, testosterone deficiency is unique because symptoms are not always well defined. This warrants casting a wider net to identify a treatable condition. Symptoms such as depression, fatigue, and inability to perform vigorous activity are related to low testosterone levels, whereas there is an inverse relationship between the number of sexual symptoms and testosterone levels.

On the other hand, Dr. Fugh-Berman raises concerns about overly aggressive marketing of testosterone supplements by pharmaceutical companies, such as online symptom surveys that seem designed to elicit "yes" answers from most older men.

These questions demonstrate how pharmaceutical companies use nonspecific symptoms to foster disease states and then convince physicians that these conditions are real. In this case, the disease state is marketed to consumers as Low T, and to physicians as late-onset hypogonadism.

Last September, an advisory committee to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration considered the potential cardiovascular risks for testosterone therapy and voted to exclude men with age-related testosterone declines from indications for testosterone use and to support performing additional studies to clarify cardiovascular harms. Whether clinical practice will evolve to reflect a similar level of caution is unclear. A 2013 analysis of a health insurance database showed that 25% of men prescribed a testosterone supplement never had a testosterone level checked, while other men with apparently normal levels nonetheless received therapy. At a minimum, family physicians who prescribe testosterone supplements should heed the Choosing Wisely recommendation to avoid these unsupported practices.

**

This post first appeared on the AFP Community Blog.

**

This post first appeared on the AFP Community Blog.

Tuesday, February 17, 2015

Actual causes of death in the U.S.: not what you think

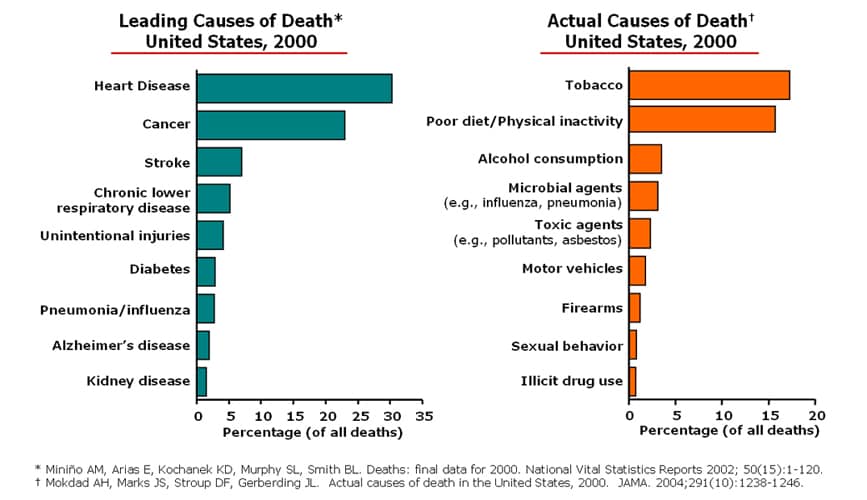

Any standard public health or medical school prevention text includes (or ought to include) some version of the figure below, which illustrates that the leading causes of death in the U.S. at the turn of the century (heart disease, cancer, stroke) were actually surrogates for what have come to be known as the actual causes of death: unhealthy behaviors such as tobacco use, poor diet, and physical inactivity.

The most effective preventive services that primary care clinicians provide, then, are not screening tests but counseling interventions that aim to change one or more of these behaviors for the better. Community-level initiatives such as tobacco-free restaurants and campuses, pedestrian-friendly cities, and increasing access to nutritious food sources play a critical role in changing health-related behaviors, too.

The most effective preventive services that primary care clinicians provide, then, are not screening tests but counseling interventions that aim to change one or more of these behaviors for the better. Community-level initiatives such as tobacco-free restaurants and campuses, pedestrian-friendly cities, and increasing access to nutritious food sources play a critical role in changing health-related behaviors, too.

Unfortunately, the impact of behavioral or "lifestyle" approaches to prevention is likely to be limited by two factors: 1) even intensive interventions produce very modest benefits; and 2) behaviors don't exist in a vacuum, but are largely shaped by economic and social circumstances. Family medicine professor and former U.S. Preventive Services Task Force member Steven Woolf has published a number of studies showing that the risk of death is strongly associated with levels of college education and income; his research team at Virginia Commonwealth University worked with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to develop an interactive County Health Calculator that illustrates how many premature deaths could be avoided by eliminating educational and income disparities.

Researchers from Columbia University went a step further in 2011 by publishing the analysis "Estimated Deaths Attributable to Social Factors in the United States" in the American Journal of Public Health. Using estimates derived from the literature on social determinants of health and year 2000 mortality data, they found that the "actual" causes of death looked like this:

1) Low education: 245,000

2) Racial segregation: 176,000

3) Low social support: 162,000

4) Individual-level poverty: 133,000

5) Income inequality: 119,000

6) Area-level poverty: 39,000

Clearly, we know a great deal more about successful strategies for fighting clinical and behavioral causes of death than we do about social causes, some of which often appear intractable. But I could not agree more with the authors' conclusion that "these findings argue for a broader public health conceptualization of the causes of mortality and an expansive policy approach that considers how social factors can be addressed to improve the health of populations." The point being: poverty, discrimination, and low education aren't just social or political issues best left to non-clinicians - they're health issues, too.

**

This post first appeared on Common Sense Family Doctor on August 26, 2011.

**

This post first appeared on Common Sense Family Doctor on August 26, 2011.

Saturday, February 7, 2015

Once a Cesarean ... now, a vaginal delivery

A recent essay in the "Narrative Matters" section of Health Affairs by physician and health policy researcher Carla Keirns highlighted the challenges that even a highly educated, well-informed patient faces in achieving the desired outcome of a vaginal childbirth, especially if her pregnancy is classified as high risk. Dr. Keirns, whose pregnancy was complicated by "advanced maternal age" (40) and gestational diabetes, narrowly avoided a Cesarean delivery by obstetricians who often seemed to be "watching the clock" more than assessing her individual circumstances. She observed how the "Cesarean culture" of medical practice overshadows the ideal of shared decision-making about delivery preference:

I was naked and uncomfortable, had invasive lines in place, and hadn’t slept or eaten in three days. If a doctor I trusted, instead of one I didn’t know, had suggested a cesarean forty-eight hours into my labor induction, I might have agreed. If they had told me that my baby’s life or health was in jeopardy, I would have consented to anything. The vision of the empowered consumer, or even the autonomous patient, is laughable under these circumstances.

American Family Physician's February 1st issue featured a review article on counseling and complications of Cesarean delivery and a concise summary of the American Academy of Family Physicians' updated clinical practice guideline on planned vaginal birth after Cesarean (VBAC). The review article, authored by Drs. Jeffrey Quinlan and Neil Murphy, noted that Cesareans represent nearly one-third of all deliveries in the U.S., with the most common indications being elective repeat Cesarean delivery (30%) and dystocia or failure to progress (30%).

Once a woman has had one Cesarean delivery, she faces considerable pressure from the medical system to choose repeat Cesarean deliveries in subsequent pregnancies. A 2014 article in The Atlantic explained why the dictum "once a Cesarean, always a Cesarean" increasingly holds true despite good evidence that planned VBAC is safe for, and desired by, most women. After the American College of Obsetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) published guidelines in 1996 (later challenged by the AAFP) recommending that in-house surgical teams be "immediately available" during planned VBAC, many hospitals stopped allowing women to attempt labor after a Cesarean. Even though ACOG now acknowledges that there is no evidence that hospitals with fewer resources have worse maternal or neonatal outcomes from planned VBAC, these restrictive institutional policies have remained in place.

After our first child was born by Cesarean section, my wife, who is also a family physician. proceeded to have three consecutive uncomplicated vaginal deliveries after the age of 35. To change the culture of medicine to support this kind of outcome, and to reduce the overall frequency of Cesarean deliveries, patients, physicians, and hospitals must advocate for aligning medical protocols with the best evidence and putting mothers and babies back at the center of care.

**

This post first appeared on the AFP Community Blog.

I was naked and uncomfortable, had invasive lines in place, and hadn’t slept or eaten in three days. If a doctor I trusted, instead of one I didn’t know, had suggested a cesarean forty-eight hours into my labor induction, I might have agreed. If they had told me that my baby’s life or health was in jeopardy, I would have consented to anything. The vision of the empowered consumer, or even the autonomous patient, is laughable under these circumstances.

American Family Physician's February 1st issue featured a review article on counseling and complications of Cesarean delivery and a concise summary of the American Academy of Family Physicians' updated clinical practice guideline on planned vaginal birth after Cesarean (VBAC). The review article, authored by Drs. Jeffrey Quinlan and Neil Murphy, noted that Cesareans represent nearly one-third of all deliveries in the U.S., with the most common indications being elective repeat Cesarean delivery (30%) and dystocia or failure to progress (30%).

Once a woman has had one Cesarean delivery, she faces considerable pressure from the medical system to choose repeat Cesarean deliveries in subsequent pregnancies. A 2014 article in The Atlantic explained why the dictum "once a Cesarean, always a Cesarean" increasingly holds true despite good evidence that planned VBAC is safe for, and desired by, most women. After the American College of Obsetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) published guidelines in 1996 (later challenged by the AAFP) recommending that in-house surgical teams be "immediately available" during planned VBAC, many hospitals stopped allowing women to attempt labor after a Cesarean. Even though ACOG now acknowledges that there is no evidence that hospitals with fewer resources have worse maternal or neonatal outcomes from planned VBAC, these restrictive institutional policies have remained in place.

After our first child was born by Cesarean section, my wife, who is also a family physician. proceeded to have three consecutive uncomplicated vaginal deliveries after the age of 35. To change the culture of medicine to support this kind of outcome, and to reduce the overall frequency of Cesarean deliveries, patients, physicians, and hospitals must advocate for aligning medical protocols with the best evidence and putting mothers and babies back at the center of care.

**

This post first appeared on the AFP Community Blog.

Monday, February 2, 2015

Project C.A.R.E.S. offers an innovative solution

It's rare that an article published in Business Insider "goes viral" in my Twitter and Facebook networks, but "Why Your Doctor Always Keeps You Waiting," by family physician Sanaz Majd, touched a raw nerve among friends and colleagues. In the article, Dr. Majd described "a day in the life of Dr. Tardy," a caring, competent family doctor who "doesn't like to take any shortcuts when it comes to patient care" and always seems to be running late. This hypothetical physician's typical half-day schedule consists of seeing patients in 20-minute time slots regardless of how much time they really need. The patients' complaints are the norm for a primary care practice: diabetes, heartburn, high blood pressure, depression, upper respiratory infections. By the end of the morning, Dr. Tardy is running more than a hour late.

By the time Dr. Tardy ends her morning, she is scheduled to see her first patient of the afternoon. It's a relief to reset the schedule once again, but this means that not only does she not have a break in the day (which doesn't really bother Dr. Tardy), but she also has no time for returning patient messages, reviewing lab results, or refilling prescriptions. This means tacking on about 2 hours at the end of her day to complete these tasks after her jam-packed afternoon schedule. And this is a typical morning for a primary care physician in the United States. Are you tired yet?

Keep in mind that the typical family doctor adheres to this grueling schedule most days of the week and earns a small fraction of a subspecialist's or hospital executive's salary, and it is unsurprising that despite a growing shortage of primary care physicians, family and general internal medicine residency programs struggle to recruit U.S. medical graduates to fill their existing slots, much less expand to meet anticipated future demand.

How to make a family medicine career more appealing and sustainable is a big project with a long-term horizon. But what can we do right now to reduce patients' waiting times while we wait for our current health system to transform into something resembling sanity? One of my residents, Dr. Troy Russell, is tackling the problem of redundant medical history taking with an innovative solution called Project C.A.R.E.S. (Communities Aided by Research and Education Solutions). In brief, he proposes to provide patients at with automated check-in kiosks that can transfer self-reported health history information directly into their electronic medical records, and measure the effect of this intervention on waiting times and patient satisfaction. If this pilot project is successful, it could inspire other underserved health clinics across the country to do the same. Please read more about the project and consider helping him and his team reach their 30-day fundraising goals to make this idea a reality.

**

UPDATE 2/10/15 - Possibly due to the widespread interest that Dr. Russell's social media campaign generated in Project C.A.R.E.S., Fort Lincoln Family Medicine Center's parent institutions have agreed to fund this project internally. The private fundraising campaign has been suspended, and all donations to date will be refunded.

By the time Dr. Tardy ends her morning, she is scheduled to see her first patient of the afternoon. It's a relief to reset the schedule once again, but this means that not only does she not have a break in the day (which doesn't really bother Dr. Tardy), but she also has no time for returning patient messages, reviewing lab results, or refilling prescriptions. This means tacking on about 2 hours at the end of her day to complete these tasks after her jam-packed afternoon schedule. And this is a typical morning for a primary care physician in the United States. Are you tired yet?

Keep in mind that the typical family doctor adheres to this grueling schedule most days of the week and earns a small fraction of a subspecialist's or hospital executive's salary, and it is unsurprising that despite a growing shortage of primary care physicians, family and general internal medicine residency programs struggle to recruit U.S. medical graduates to fill their existing slots, much less expand to meet anticipated future demand.

How to make a family medicine career more appealing and sustainable is a big project with a long-term horizon. But what can we do right now to reduce patients' waiting times while we wait for our current health system to transform into something resembling sanity? One of my residents, Dr. Troy Russell, is tackling the problem of redundant medical history taking with an innovative solution called Project C.A.R.E.S. (Communities Aided by Research and Education Solutions). In brief, he proposes to provide patients at with automated check-in kiosks that can transfer self-reported health history information directly into their electronic medical records, and measure the effect of this intervention on waiting times and patient satisfaction. If this pilot project is successful, it could inspire other underserved health clinics across the country to do the same. Please read more about the project and consider helping him and his team reach their 30-day fundraising goals to make this idea a reality.

**

UPDATE 2/10/15 - Possibly due to the widespread interest that Dr. Russell's social media campaign generated in Project C.A.R.E.S., Fort Lincoln Family Medicine Center's parent institutions have agreed to fund this project internally. The private fundraising campaign has been suspended, and all donations to date will be refunded.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)