Looking for some good reads for this holiday season and the coming year? Here is my annual top ten list of health and medicine-related books (read, not necessarily published, in 2019), in alphabetical order. I've provided links to the publishers' websites for your convenience, but I don't receive any financial incentives or extra web traffic if you buy these books from them. So if one or more catch your fancy, feel free to pick up a used copy on Amazon or a free one at PaperBackSwap or your local library.

**

1. The Addict: One Patient, One Doctor, One Year, by Michael Stein

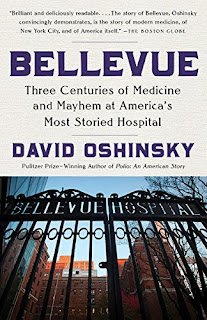

2. Bellevue: Three Centuries of Medicine and Mayhem at America's Most Storied Hospital, by David Oshinsky

3. Crisis in the Red Zone: The Story of the Deadliest Ebola Outbreak in History, and of the Outbreaks to Come, by Richard Preston

4. Deep Medicine: How Artificial Intelligence Can Make Healthcare Human Again, by Eric Topol

5. Patient H.M.: A Story of Memory, Madness, and Family Secrets, by Luke Dittrich

6. Priced Out: The Economic and Ethical Costs of American Health Care, by Uwe Reinhardt

7. Radical: The Science, Culture, and History of Breast Cancer in America, by Kate Pickert

8. Recapturing Joy in Medicine, by Amaryllis Sanchez Wohlever

9. Vaccines Did Not Cause Rachel's Autism: My Journey As a Vaccine Scientist, Pediatrician, and Autism Dad - Peter Hotez

10. Well: What We Need to Talk About When We Talk About Health, by Sandro Galea

Thursday, December 26, 2019

Saturday, December 14, 2019

Proposals to lower prescription drug prices: too little, too late?

A bright spot in the annual U.S. health spending report published last week by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) was a 1% decrease in retail prescription drug costs from 2017 to 2018, due to greater use of generics and a slower rise in brand-name prices. According to CMS, this was the first time that these costs have declined since 1973. A previous American Family Physician Community Blog post described ongoing efforts by physician groups, payers, and government to restrain rising drug prices; a 2017 editorial reviewed actions that individual health professionals could take to help patients; and a 2019 editorial discussed the high costs of insulin and what family physicians can do. It's possible that some of these efforts are beginning to bear fruit.

Prescription drug prices vary considerably across pharmacies, geographic regions, and even within the same town or metropolitan area. A cross-sectional study of cash prices for 10 common generic and 6 brand-name drugs in the fall of 2015 obtained using the online comparison tool GoodRx (which AFP uses to estimate drug prices) found that generic drugs were least expensive in big box pharmacies, followed by large chain (more than 100 retail locations) and grocery pharmacies, while small chains (4 to 100 stores) and independent pharmacies had the highest prices. For example, the mean price of one month of generic simvastatin 20 mg was $35 at big box pharmacies, $42 at large chains, $50 at groceries, $112 at small chains, and $138 at independent pharmacies. Cash prices for brand-name drugs varied less; one month of esomeprazole (Nexium) 40 mg, for example, cost between $302 and $345 across pharmacy types.

The American College of Physicians recently joined a growing number of groups advocating that CMS be given the authority to directly negotiate drug prices in Medicare Part D, which is currently forbidden by law. In contrast, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Health System already controls prescription costs through direct negotiation and a closed formulary. A study in JAMA Internal Medicine calculated that in 2017, Medicare could have saved $1.4 billion on inhalers for asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease by paying lower VA-negotiated prices, and $4.2 billion if it had paid VA prices and instituted the VA formulary.

But what about the pharmaceutical industry's assertion that lower negotiated prices would stifle innovation and reduce incentives for drug development? In a recent commentary, Dr. Peter Bach proposed that CMS adopt a "too little" or "too late" strategy, selectively negotiating prices of drugs that have either received conditional FDA approval based on a surrogate rather than a patient-centered outcome ("too little") or have passed their guaranteed 5-year period of FDA monopoly protection ("too late"). In 2019, if CMS had negotiated the prices of the top 10 most costly drugs in each category down to those in the United Kingdom (an average savings of 57%), Dr. Bach estimated that it could have saved $1 billion on the 10 "too little" drugs and $26 billion on the 10 "too late."

The potential savings are substantial. But compared to the staggering $336 billion the U.S. collectively spent on prescription drugs in 2018, are these proposed pricing reforms too little, too late?

**

This post first appeared on the AFP Community Blog.

Prescription drug prices vary considerably across pharmacies, geographic regions, and even within the same town or metropolitan area. A cross-sectional study of cash prices for 10 common generic and 6 brand-name drugs in the fall of 2015 obtained using the online comparison tool GoodRx (which AFP uses to estimate drug prices) found that generic drugs were least expensive in big box pharmacies, followed by large chain (more than 100 retail locations) and grocery pharmacies, while small chains (4 to 100 stores) and independent pharmacies had the highest prices. For example, the mean price of one month of generic simvastatin 20 mg was $35 at big box pharmacies, $42 at large chains, $50 at groceries, $112 at small chains, and $138 at independent pharmacies. Cash prices for brand-name drugs varied less; one month of esomeprazole (Nexium) 40 mg, for example, cost between $302 and $345 across pharmacy types.

The American College of Physicians recently joined a growing number of groups advocating that CMS be given the authority to directly negotiate drug prices in Medicare Part D, which is currently forbidden by law. In contrast, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Health System already controls prescription costs through direct negotiation and a closed formulary. A study in JAMA Internal Medicine calculated that in 2017, Medicare could have saved $1.4 billion on inhalers for asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease by paying lower VA-negotiated prices, and $4.2 billion if it had paid VA prices and instituted the VA formulary.

But what about the pharmaceutical industry's assertion that lower negotiated prices would stifle innovation and reduce incentives for drug development? In a recent commentary, Dr. Peter Bach proposed that CMS adopt a "too little" or "too late" strategy, selectively negotiating prices of drugs that have either received conditional FDA approval based on a surrogate rather than a patient-centered outcome ("too little") or have passed their guaranteed 5-year period of FDA monopoly protection ("too late"). In 2019, if CMS had negotiated the prices of the top 10 most costly drugs in each category down to those in the United Kingdom (an average savings of 57%), Dr. Bach estimated that it could have saved $1 billion on the 10 "too little" drugs and $26 billion on the 10 "too late."

The potential savings are substantial. But compared to the staggering $336 billion the U.S. collectively spent on prescription drugs in 2018, are these proposed pricing reforms too little, too late?

**

This post first appeared on the AFP Community Blog.

Wednesday, December 4, 2019

The health dividend: reducing medical waste to improve population health

For most people, the term "medical waste" probably brings to mind images of discarded syringes, soiled gauze and bandages, and garbage containers filled with the ubiquitous plastic packing for sterilized instruments. They probably don't think about inconceivably large piles of money evaporating into thin air. But in addition to having the most expensive health care system in the world, the U.S. also leads the world in wasted health care spending. In a recent analysis in JAMA, Dr. William Shrank and colleagues updated prior estimates based on published literature from 2012 to 2019 and concluded that approximately 25% of national health care spending, or about $800 billion each year, is wasted. The main culprits are administrative complexity ($266 billion); excessively high prices ($231-$241 billion); failure of care delivery ($102-$166 billion); overtreatment or low-value care ($76-$101 billion); fraud and abuse ($59-$84 billion); and poor care coordination ($27-$78 billion).

These are huge amounts of money. When American life expectancy has been falling for three consecutive years after more than half a century of steady increases, it would seem that reallocation to population health initiatives of the portion of health care waste that is potentially recoverable with existing interventions, $191 to $282 billion according to the JAMA study (by comparison, annual funding for the Affordable Care Act's Prevention and Public Health Fund has yet to exceed $1 billion), would go a long way toward addressing the root causes of increasing premature deaths - problems such as poverty, segregation, and low social support which comprise the actual causes of death in the U.S.

So why don't we? In an accompanying editorial, former CMS administrator Dr. Don Berwick hit the nail on the head:

What Shrank and colleagues and their predecessors call “waste,” others call “income.” ... When big money in the status quo makes the rules, removing waste translates into losing elections. ... For officeholders and office seekers in any party, it is simply not worth the political risk to try to dislodge even a substantial percentage of the $1 trillion of opportunity for reinvestment that lies captive in the health care of today, even though the nation’s schools, small businesses, road builders, bridge builders, scientists, individuals with low income, middle-class people, would-be entrepreneurs, and communities as a whole could make much, much better use of that money.

These are huge amounts of money. When American life expectancy has been falling for three consecutive years after more than half a century of steady increases, it would seem that reallocation to population health initiatives of the portion of health care waste that is potentially recoverable with existing interventions, $191 to $282 billion according to the JAMA study (by comparison, annual funding for the Affordable Care Act's Prevention and Public Health Fund has yet to exceed $1 billion), would go a long way toward addressing the root causes of increasing premature deaths - problems such as poverty, segregation, and low social support which comprise the actual causes of death in the U.S.

So why don't we? In an accompanying editorial, former CMS administrator Dr. Don Berwick hit the nail on the head:

What Shrank and colleagues and their predecessors call “waste,” others call “income.” ... When big money in the status quo makes the rules, removing waste translates into losing elections. ... For officeholders and office seekers in any party, it is simply not worth the political risk to try to dislodge even a substantial percentage of the $1 trillion of opportunity for reinvestment that lies captive in the health care of today, even though the nation’s schools, small businesses, road builders, bridge builders, scientists, individuals with low income, middle-class people, would-be entrepreneurs, and communities as a whole could make much, much better use of that money.

Living in Washington, DC during the Great Recession of 2007-2009, I observed that the only two industries that managed to thrive and expand during those otherwise dismal years were the federal government and health care. While that was good for me personally, as a health care professional then employed by the federal government, it also meant that billions of dollars that otherwise could have contributed to the economy and individual incomes were, as Dr. Berwick noted, "captured" by the health care industry, most clearly in the form of rising costs of health insurance.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War, Presidents George H. W. Bush and Bill Clinton both talked about a "peace dividend" consisting of lower military spending that could be diverted into other government programs, used to pay down budget deficits, or returned to the people in the form of lower taxes. Although it is debatable how much the military-industrial complex really shrunk in the 1990s, the gargantuan health care-industrial complex is likely to be at least as tenacious, if not more, in resisting efforts to reduce wasteful spending in order to generate a "health dividend" for all Americans.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)